We need a real European High Speed Rail Network

The climate problem of Europeans flying everywhere is clear by now, but it would be a lot smaller if Europe had a real European High Speed Network.

The climate problem of Europeans flying everywhere is clear by now: Co2 emissions per kilometre travelled are ridiculously high: 6–8 times more than that of rail. Meanwhile, we live on a small, densely populated continent eminently suitable for High Speed Rail (HSR). Anyone that’s ever taken a direct HSR connection, is astounded by the comfort and convenience of whizzing from city centre to city centre. It is also a proven technology using just 20, or even 0 grams CO2/km when powered by renewable energy.

Cars will also electrify, but HSR is a faster, more comfortable, 50 times safer alternative. For the aviation sector, the prospects are poor. Without decarbonising, aviation could account for 22% of all global CO2 emissions by 2050. Fuel efficiency in the air travel sector is improving by just one percent a year, carbon offsetting is a red herring, and electric flights and hydrogen e-kerosenes are decades away. While we encourage innovation in this field, we simply cannot wait for sustainable flying to be fully developed, approved and rolled out at scale. The European Commission has acknowledged this, and set a goal for doubling and tripling HSR by 2030 and 2050.

However, rail has a market share of just 8% of all European passenger kilometres travelled. Only 1 in 3 of short haul flights have a train alternative under 6 hours.

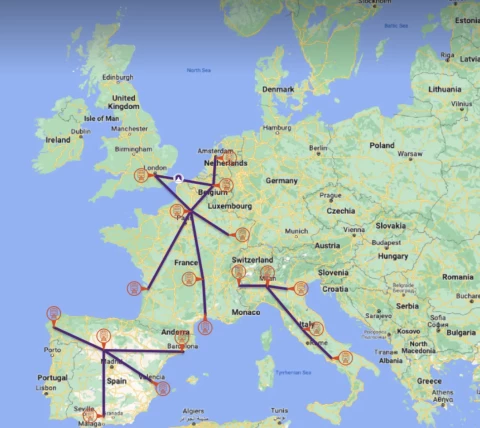

The author trained it from Amsterdam to Dublin, Barcelona, and Milan in 2022. All are in the top 10 for ’most flown routes’ from Amsterdam, and some 1000 km as the crow (or plane) flies. Though they can be reached in a single day of travel, the problems soon became evident. In this article, we will discuss the top 4 frustrations, many of which can be addressed in the short term, with minimal hard infrastructure investment.

Hard to book

Expensive

Stops & transfers

Hard infrastructure

1: Hard to book — There is no single app from which you can book an end-to-end journey, as railway companies do not share their timetables. To the frustration of both the author and EU Commission VP Frans Timmermans, getting a cross-border ticket resembles solving an intricate puzzle, with multiple tickets sourced from different websites. Mr. Timmermans has given a verbal ultimatum for train companies to solve this by the end of 2022, or he will ’enforce it legally’.

What needs to be done?: The EU must legally enforce railway companies to provide open access API to all their timetables, routes & tickets. This is an easy fix, and must be done asap.

When?: 6–12 months.

2: Expensive — Though HSR is already price-competitive with flights on select direct lines, the author paid some 300–400 euros for his three longer round trips, resulting in a 2 to 3 times higher price than flying. A reason is that there is no kerosene tax (a few dimes per litre) like there is on petrol (a few euros per litre), disregarding the negative externalities of flying. Most countries do not levy a CO2 tax on kerosene under a 1944 (!) UN agreement. Since 2003, it is optional for EU countries to levy a tax, but only the Netherlands does.

What needs to be done?: Taxation, taxation and taxation. Three clear options exist. First, VAT. Airline tickets are on a 0% VAT rate, but train tickets are subject to VAT. European nationals and the EU must target a 0% VAT levy on train tickets, focusing first on international and domestic flight-corridors. Second, CO2 tax on kerosene must be made obligatory rather than optional. Third, a progressive frequent flyer levy (FFL) and/or flight tax, to discourage heavy users.

Heavier taxation, or a full prohibition should come next on routes with solid, proven rail connections. This is also recommended by the 200 ordinary EU citizens in the 2021 EU conference on the future of Europe. France has led the way, banning domestic flights where a rail connection exists of under 2.5 hours. The raised taxes should be used to further connect, expand, and subsidise European HSR.

When?: 12–24 months.

3: Stops & transfers — As HSR networks are poorly connected across borders, trains that buzz along at 300km/h, halting only in major cities, suddenly slow to 120km/h and stop in every regional town. The reason is that national HSR operators and national governments intertwine regional and international interests, slowing down long-distance travellers.

Furthermore, on two of the author’s three trips, there was a transfer from one train station to another in the city of Paris, forcing a luggage-dragging metro ride and adding 2 hours of travel time. This problem does not exist for national rail travel, which usually from the next platform within a reasonable time frame, and is therefore is emblematic of the national focus of HSR rail operators, who care little about the connections of international travellers.

Once transfers are aligned from the same station, and within a reasonable timeframe, the chance of delay still remains. This adds to traveller stress, as they often move from one railway operator to another. If you travel nationally, you know you are always allowed onto the next train. For international travel, with assigned seating, the rules are not clear.

What needs to be done?: First, we need to appoint a European corridor coordinator, with the priority task to reduce travel time between most travelled metropolitan corridors. Second, this effort needs to be expanded into a pan-European rail authority. These institutions need to be given the mandate to create a new supranational Public Service Obligations for important connections.

The new EU corridor coordinator and EU rail authority must minimise stops by i) disentangling local from long-distance travel, and ii) enforce the optimal connection between international trains on important metropolitan corridors. To do this, an EU-enforced system of scheduling alignment should be introduced. Such a joined IT system would enforce the alignment of travel itineraries and train stations, and oblige train operators to serve travellers regardless of delays, at no extra cost.

When?: 12–24 months (EU corridor coordinator) and 2–4 years (EU rail authority).

4: Hard infrastructure — Europe now has three HSR ‘hubs’, centring around Paris, Milan, and Madrid, which are not connected. This forces travellers to switch to slow trains, or continue their HSR rail at a far reduced pace. This is a matter of hard infrastructure upgrade.

What needs to be done?: Connecting the Paris, Milan and Madrid hubs should be made an infrastructural priority, connecting 270 million citizens. The Lyon-Milan line is now in preparation, reducing travel time from 7 hours to 4. After this, this unified network should be expanded into a truly pan-European network, connecting 500 Million Europeans. Once Europe is connected, HSR night trains would quite easily increase the travel range to some 2000km. Funds from Europe, e.g. charged on flight taxation, should be used for co-financing.

When?: 1–20 year

The European Union is aware that long-distance rail travel needs to be improved, and late 2021 published a detailed report of the current state. We encourage this endeavour and argue for high priority action to address the challenges encountered in today’s EU HSR system.

Hard to book → API to timetables & routes (6–12 months)

Expensive → Tax CO2, invest in rail (12–24 months)

Stops & transfers→ EU coordinator & rail authority (12–48 months)

Infrastructure upgrade → (1–20 years)

This article was authored by Paul van Bommel.