The limits to degrowth

In May 2023, MEPs, academics and advocates met in Brussels to discuss our future #BeyondGrowth. How can the EU lead us towards green growth?

In May 2023, 20 MEPs organised ‘Beyond Growth’, a 3-day event in Brussels. Indeed, there is no denying that Europe finds itself in a conundrum. Since the industrial revolution, we have enriched ourselves by burning lots of fossil fuels as a source of energy. We have been heating up our planet and destroying our ecosystems doing so, and worse, we have inadvertently laid out a destructive path for developing countries to follow.

Whilst high and lower-income countries must agree on a common course, much of the debate on future sustainability focuses on either degrowth, the concept of scaling down the scope of our economic activities, or on green growth, decoupling economic growth from environmental destruction.

Often, the debate tailspins into the larger question of social fairness, of the huge emission gap between the haves and have-nots. This debate is certainly justified - the greenhouse gas emissions of the top 1% are 1.5 times those of the entire bottom half of the world’s population.

The theory of degrowth holds that high-income economies consume natural resources and available energy at unsustainable rates. NGOs like the European Environmental Bureau, are sceptical that economic growth can coexist with environmental sustainability. As the global economy is structured around GDP growth objectives, we are locked in a perpetual cycle of increased production, much of which is superfluous. The degrowth movement asks: does a middle-class family need a new car every few years? Do they need continuous intercontinental holidays? GDP, they argue, has been used as the metric to measure economic growth but is limited as an accounting principle. It needs to be complemented with metrics that evaluate human wellbeing in a broader sense.

The proposed solution is a scale-down of the economic activity. Clearly, much is to be said for a decreased consumption of high-emission products like fossil fuels, meat, cement or steel. With diminished consumption in high-income countries, resources and energy could be freed up for low and middle-income countries, which still need physical production to establish growth.

Rather than encouraging our economies to decline, what we should focus on is the type and characteristics of growth we seek in society.

The criticism of an exclusive focus on GDP is fair enough. Modern economists like Kate Raworth (Doughnut Economics) have a strong point when they point to the destructive tendencies of growth-central economics. However, neither should we focus on diminishing GDP, as economic growth in itself is not the culprit. Growth can also be the result of human inventiveness, a product of innovation and technology at the service of human needs and wants, generating value and spreading across society. What matters is the type of growth an economy strives for.

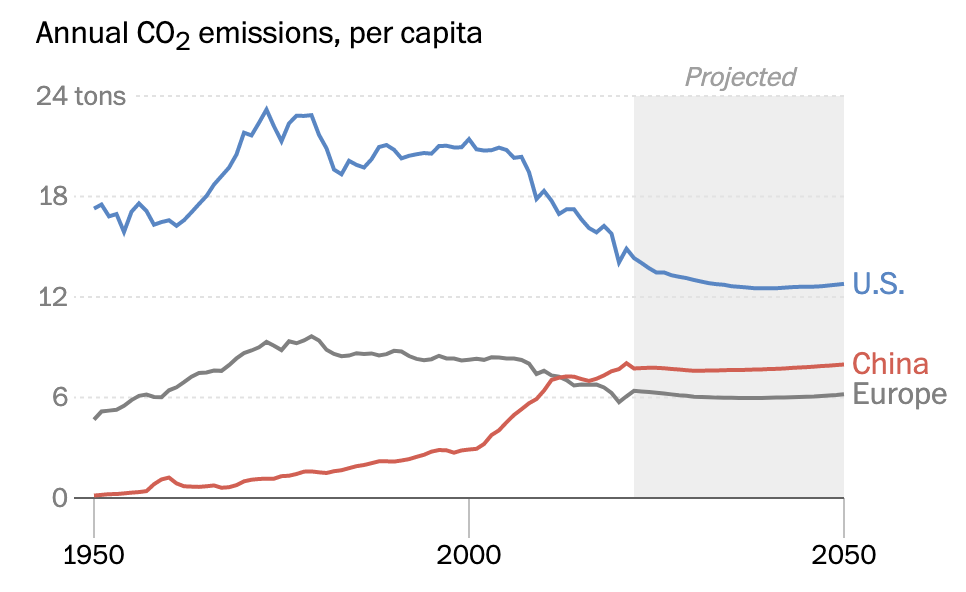

The degrowth movement under-emphasises this important point: that GDP growth is not inextricably linked to a rise in CO2 emissions. It is certainly true that lower and middle-income countries increase CO2 emissions as they develop their (fossil-based) economies. China is a clear example of this.

Figure: China CO2 per Capita higher than EU

However, emissions per capita of higher income countries like the US, EU and UK have already halved from their respective peaks. Eastern European emissions have fallen since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and even China’s are now stagnating as they turn to renewable energy sources and become more efficient in the amount of energy needed per unit of output.

However, emissions per capita of higher income countries like the US, EU and UK have already halved from their respective peaks. Eastern European emissions have fallen since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and even China’s are now stagnating as they turn to renewable energy sources and become more efficient in the amount of energy needed per unit of output.

With investment in renewables and electrification, more gains can soon be realised, boosting long-term growth. An economy that must scrimp and save to conserve energy is less dynamic than one in which power is green, abundant and cheap.

The message ‘less stuff for everybody’ is not only a vote-loser, it is also dangerous. It inadvertently helps anti-environmentalists keen to spin the narrative that protecting the environment is incompatible with rising living standards. Ultimately, innovation is the solution to our current predicament.

While in many sectors it is possible to decouple growth from environmental harm, this is not an automatic process. Policies need to be shaped to encourage the use of technologies that cause less environmental damage. This can be in the form of encouraging infrastructure investment like the EU Green Deal, InvestEU or the US Inflation Reduction Act. It can also be spurned by legislative frameworks like the EU’s Fit for 55 plan.

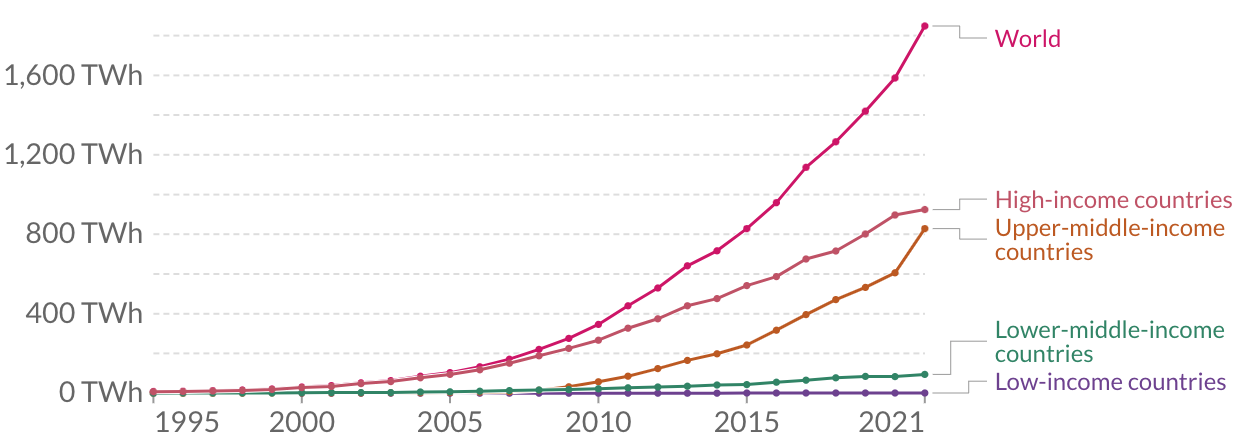

The task now is to accelerate the decoupling of economic activity from CO2 emissions. One reason for optimism is that so far it has happened without colossal outlays or political consensus. Electricity generation is decarbonising exponentially, with much faster than expected cost declines from solar and wind.

Figure: Wind power generation

Figure: Solar power generation

Figure: Solar power generation

Many of the West’s fastest improvers have emissions-trading schemes or other forms of carbon pricing. For higher-income countries, the rapid spread of renewables in electricity generation, as well as electrifying the heating of homes, cars and other transport, will make an even bigger difference. Importantly, as richer countries develop technologies and drive down cost, they clear the way for lower income countries to develop sustainably.

But poorer countries are industrialising in different ways from their predecessors as well. India and Vietnam, low-income economies which are stealing export business away from China, are already considerably greener than their economic rival. In 2007, when China’s economy was roughly as big as India’s is today, it emitted around twice as much carbon dioxide. India and Vietnam are still powered by coal, but the difference is they are making much more efficient use of it. And now they’re developing their economies, renewables are becoming the most economical option.

Europe’s leading role

The European Union represents some 16% of the world economy. Thinkers like Mariana Mazzucato and Bill Gates rightly argue that, as huge consumers (of fuel and raw materials, or by subsidising transport), European governments can help green startups succeed.

Paradigm shifts only occur because of publicly-allocated R&D funding and a committed buyer, in the case of the internet, both were in the form of the US government. Likewise, in order to accelerate green innovation, developed economies like the EU, US and Japan must take the lead.

Regulation of both existing and new technologies is also important, the most harmful sectors of our economy must adapt or decline to secure green growth for Europe as a whole. The EU is the world’s regulatory powerhouse, with economies worldwide replicating the Union’s legislation, institutions, and litigation.

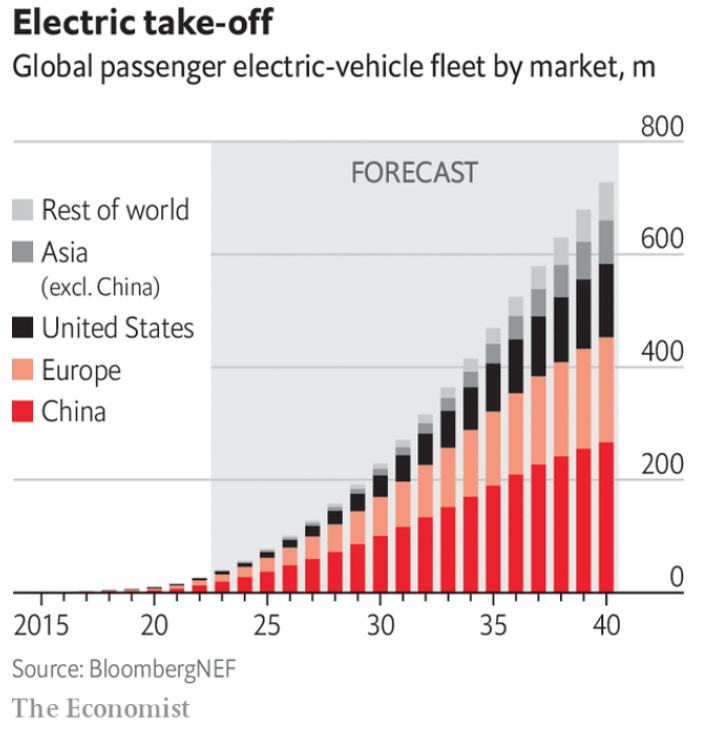

An example of countries leading both innovation and regulation is in the rise of electric cars. America’s GM (EV1, 1996) first mass-produced them, while Tesla (Roadster, 2003) began the revolution in earnest. Since then, European and overwhelmingly Chinese firms have shifted the majority of production to electric vehicles. Meanwhile, EU regulators will abolish the sale of fossil fuel cars by 2035, China is demanding that 20% of cars must be EVs by 2025, and even America recently unveiled plans for strict limits to vehicle emissions. The ripple effect of this innovation and regulation will be felt around the globe.

It is through continued regulation, goal-setting and investment that the European Union must drive green growth to the benefit of all economies, including today’s lower-income countries, which will inevitably develop in the coming decades. Let's lay down the tracks below, so they can and can do so sustainably.

It is through continued regulation, goal-setting and investment that the European Union must drive green growth to the benefit of all economies, including today’s lower-income countries, which will inevitably develop in the coming decades. Let's lay down the tracks below, so they can and can do so sustainably.

EU corporate taxation: The green transition needs to be financed. The Union needs to introduce EU-wide tax harmonisation, ultimately leading to European corporate taxes that can be centrally invested. This taxation should be progressive by turnover.

EU energy market: The Union needs to move to a single, renewable-first energy market. The union must regulate towards achieving this goal.

EU subsidy: The Union need to stop subsidising unsustainable business practices, and heavily subsidise sustainable practices, be it in agriculture, energy generation or industry.

Article by Paul van Bommel.